Example of a translation error: In China there is a restaurant called “Translate Server Error” because the restaurant owner used an online website to translate the Chinese word for “restaurant” into English.

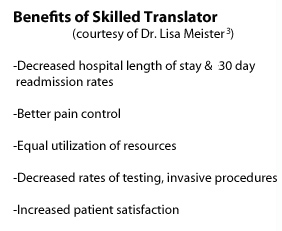

We know using skilled translators has many benefits such as improving patient outcomes, satisfaction, pain control, and number of medical errors (see sidebar below). In the United States, healthcare providers have increasingly been encountering patients who have limited English proficiency (LEP), with 15% of people reporting they spoke English “not well” and an additional 7% spoke English “not at all.”1 In 2006 New York State required all hospitals to provide skilled translators free of charge to patients.2 Several surveys have shown skilled translation services have been underutilized. Dr. Lisa Meister conducted a survey of 52 ER residents in 2012 and found that 56% of residents did not use professional services for encounters with LEP patients.3 A national survey in Annals of Emergency Medicine also found a propensity to use unapproved translators and a lack of training on appropriate medical translation policies.4

Evidence for using skilled translators is bountiful, and there is little more I can add in support of their use without inducing nausea. Instead I wish to entice readers with something appetizing, sapid, and memorable: Three cautionary tales demonstrating the high cost of language barriers in medical malpractice. Physicians who experience language barriers may deliver “delayed, incorrect, or improper medical care, potentially leading to a costly, time-consuming medical malpractice lawsuit”. 5,6

Three Cautionary Tales:

Case 1At the end of the day, using professional translators isn’t just about avoiding lawsuits, it’s about doing what’s best for the patient. People come to our ER when they’re sick, vulnerable, and afraid. Using a professional translator helps us better care for our patients by minimizing barriers as well as letting our patients know we really care about what they have to say.

By Dr. Wendy Chan

References

- Ryan, Camille. Language Use in the United States: 2011. N.p.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2003. Print.

- Pub. L. 88-352, Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Sec. 601, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 252.

- Meister, Lisa, MD. “Patients with Limited English proficiency in the Emergency Department: Why We Can and Should Do Better.” SUNY EM Senior Lecture. 21 Oct. 2012. Lecture.

- Flores, Glenn, Milagros Abreu, Cara Pizzo Barone, Richard Bachur, and Hua Lin. “Errors of Medical Interpretation and Their Potential Clinical Consequences: A Comparison of Professional Versus Ad Hoc Versus No Interpreters.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 60.5 (2012): 545-53. Web.

- Van Kempen, Abigail. “Legal Risks of Ineffective Communication.” Virtual Mentor. AMA, Aug. 2007. Web. 1 Sept. 2014.

- Lee KC, Winickoff JP, Kim MK, Campbell EG, Betancourt JR, Park ER, Maina AW, Weissman JS. “Resident physicians’ use of professional and nonprofessional interpreters: a national survey.” JAMA. 2006;296(9):1050-3.

- “Quadriplegic to Receive Up to $71 Million in Suit.” The Palm Beach Post, 5 Nov. 1983. Web. 1 Sept. 2014.

- Harsham P. A misinterpreted word worth $71 million. Medical Economics. 1984;61(5):289-292.

- Quintero vs Encarnacion et al. U.S. Court of Appeals 10th Circuit. 29 Nov. 2000. Print.

- Santora, Marc. “Caught in the Health Care Maze: A Korean Family’s Story.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 25 July 2004. Web. 1 Sept. 2014.

- Kwan, Kelvin, JD MPH. “The High Costs of Language Barriers in Medical Malpractice.” National Health Law Program (2010): n. pag. Web. 1 Sept. 2014.

wendyrollerblades

Latest posts by wendyrollerblades (see all)

- EM-CCM Hematology 7/22/2015:Treating DIC - July 27, 2015

- Critical Care: Recent Trials in Sepsis - May 1, 2015

- TASER Conducted Electrical Weapon Injuries - March 9, 2015

- Racially Biased Pain Control in the ED - December 15, 2014

- Cyra Whaa?!: Cautionary Tales About ER Folks Who Didn’t Use Skilled Translators - September 22, 2014